Rummaging through a trunk of papers inherited from my Dad, I found a map of India from his time in the 45thCavalry during WW2. Looks like he bought it in Jhansi, just south of Lucknow, a snip at 15 rupees. He marked his travels in crayon, a convincing orange zig zag across the country. It is an itinerary that any 19 year old would be proud. Up to the North West Frontier Province (before partition of course) across to Calcutta, into Burma, but also down south to Coonor in the Nilgiri hills, Madras, and Bombay; loads of places. A sort of gap year really, save that it was two, and lots of it was in a tank, some in a jungle fighting the Japanese. But there is something else telling about the map, the logo of The Survey of India on the front, with the two names of Lambton and Everest.

It makes a good story.

By mid-eighteenth century there were various maps of parts of India with astrological measurements being used to confirm the location of major cities and topographical maps of key areas. However, it was Lambton, a military surveyor, who persuaded the powers that be, that a proper trigonometric survey of the whole of India was needed, a massive project by any measure, but which Lambton estimated could be completed in 5 years. He set out to persuade his superiors, but before he could start he needed some kit, in particular an accurate way of measuring distance, a zenith sector telescope and a theodolite.

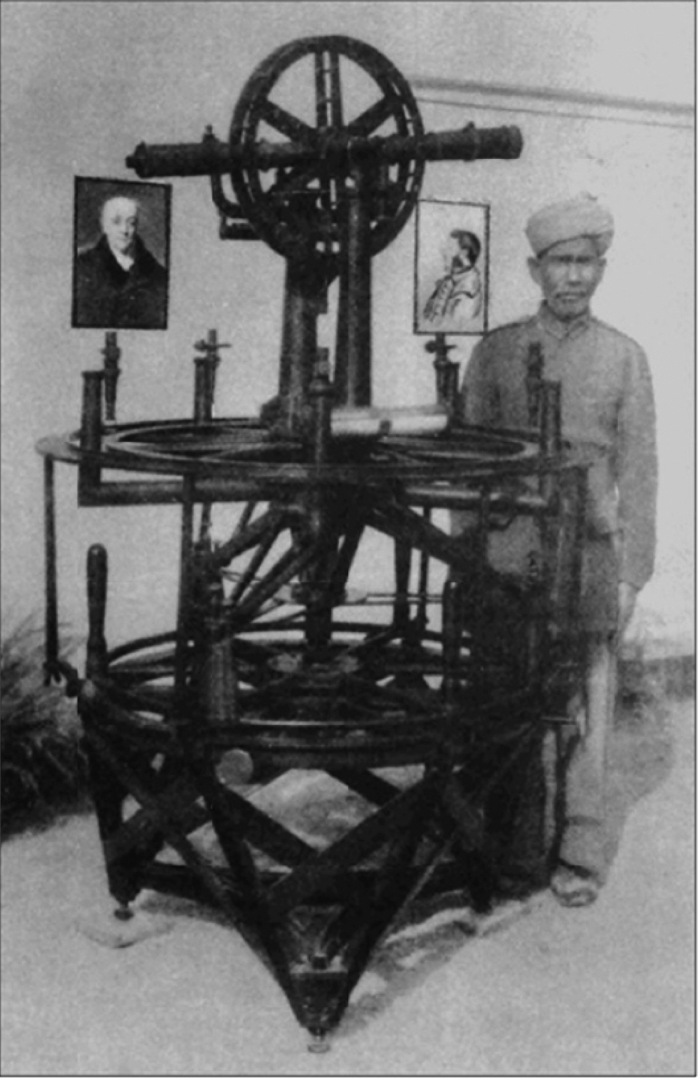

Not just any theodolite; the biggest swankiest one he could find made by the London instrument maker William Carey, 36 inches across with micrometer adjustment and weighing in at over 500kg.

He ordered it on Amazon but alas the ship on which it was travelling was captured by the French and impounded. Crisis! Happily, lines of communication were such that after pleas that the mysterious boxes contained scientific instruments not weapons, they were released, the French presumably thinking that when the captured more Indian territory they would need good maps.

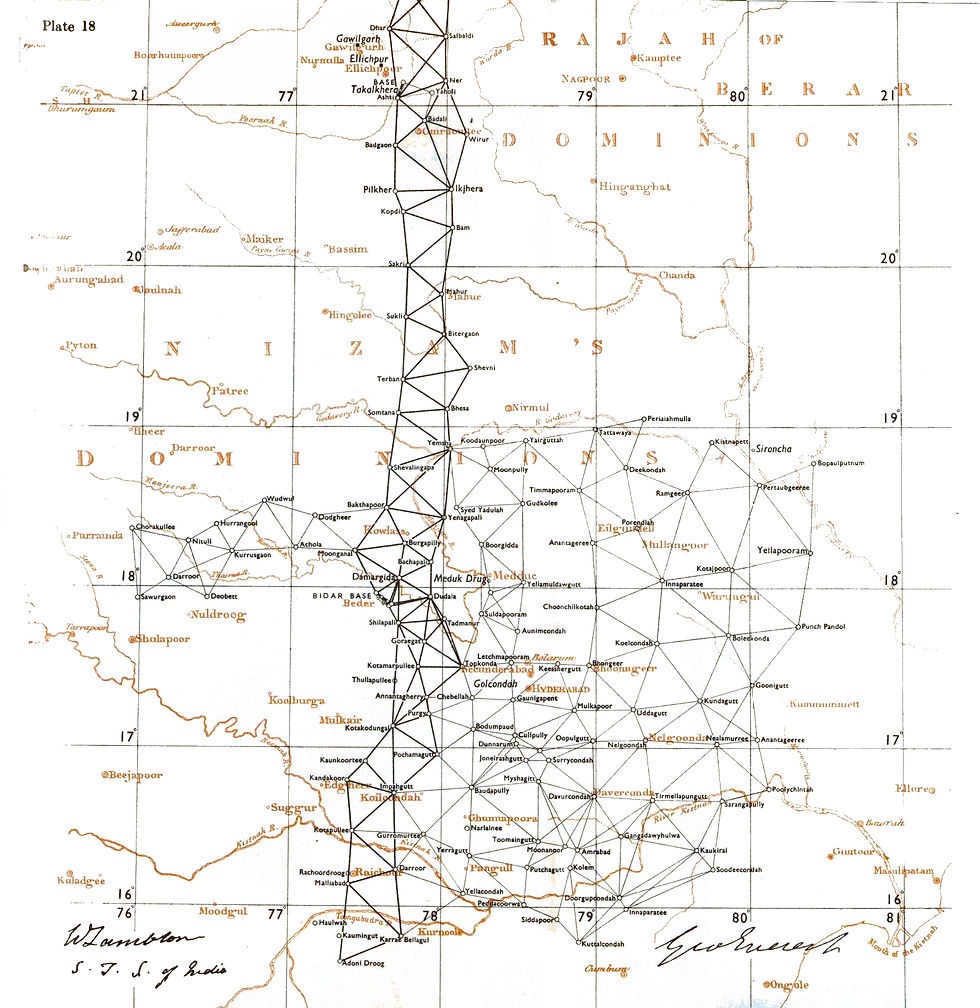

The idea of a trigonometric survey is simple: if you know the length of one side of a triangle and the angles at each end you can work out the length of the other two sides. But to start with you must measure the length of the first side very accurately. Enter the Ramsden chain, 100 steel links each 1ft in length accurate to fractions of an inch. Simply lay this across several miles of Indian scrub land, keep it out of the sun to avoid temperature change, ensure it is dead straight using a special telescope and you’re getting close. Lambton’s base triangle started near what is now Chennai Airport and finished 7½ miles to the south. It took them 57 days. Accuracy was estimated at ± 3 inches over five miles. Then all you need do is measure accurately the angles to a distant landmark that can be seen from both ends, using your theodolite, taking into account refraction errors, which require measurement of humidity using grasses or grains of rice, the curvature of the earth, and ambient temperature . . .

Lambton was able to make his first triangle and begin calculations. Then all that was needed was to carry his equipment to the third point (usually a hill or rocky landmark) and repeat the operation using the calculated distance as the new triangle baseline. Continue the above for seventy years, (at one stage employing 700 people) and you’re done.

Lambton died on the job, as it were, to be succeeded by his assistant George Everest, but it still wasn’t finished on his retirement in 1843. The survey was finally completed in 1871, very late and way over budget. Think HS2!

Early in his tenure Everest realised that he needed help from a competent mathematician, and was recommended Radhanath Sikdar, a genius wunderkind from Calcutta. As the team approached the Himalayas it became possible to measure the height of visible peaks. At the time Kanchenjunga was thought to be the world’s highest mountain but from his calculations Sikdar realised that another mountain, Peak XV, seemed higher.

Six further observations in 1852, from different sites, confirmed a height of exactly 29,000 feet, taller than Kanchenjunga and K2. Waugh (Everest’s successor) added two feet because he thought no one would believe the round number. It was given the name Everest. This figure remained the official height until further calculations produced a figure of 29,029 in 1955. How much more respectful would it have been if it had been called Mount Sikdar, a brilliant but modest pedagogue whose role in the exercise was never fully appreciated.

****************

But now we are in Madurai, where father didn’t visit, (Madura on his map) but passed close by on his way to Colombo. Opening the map out, (still without tears on the creases) Madura seems a long way down, so very far south. What many don’t realise is that India also has a north/south divide, just as we do – and the US and Italy for that matter. The five southern states think differently, vote differently and surprisingly are more productive than the northern block, which leads to resentment and 'us and them' thinking. Modi and the VJP are much less secure here in the land of temples and Tamils, but with tourist charms to rival the Golden Triangle. It is peaceful and green and with roads rather better than when Dad was here, though I doubt the driving has improved.

We are lodged in the Heritage Hotel to visit the temple, one of the great Hindu sites in the whole of India. I like the hotel because it hasn’t been overly westernised. It is not another Hyatt or Hilton, or even Best Western or Ibis for that matter. None of this Leading Hotels of the World nonsense, achieving mindless unwelcoming uniformity, whilst ensuring your room will be too cold in the summer and too hot in the winter.

Our guide at the temple is as hard to read as Tamil script. He could be an academic, but equally could be an autodidact from a slum. He gives little away. Tall and lean, partially shabby. I worry about his bloodshot eyes and pinpoint pupils (perhaps I am getting a bit too Eric Ambler here!) but his clothing gives nothing away; he would be anonymous on any Indian street. He is informative and answers our questions without being conciliatory and softens his serious style after we make a few jokes. I think he is a good Hindu, he has that aesthenic unfed look about him, as though he needs a good meal rather than a banana and a chapati.

The temple is huge, and ancient, its footprint certainly Dravidian. The monumental towers, with what westerners often consider to be vulgar, painted stucco figures, are also of great age, but surprisingly were only painted in the middle of the twentieth century. One has to ask why?

When we emerge ninety minutes later to re-join our shoes and our phones and cameras – all of which we had to leave at the door – we understand more about how a temple fits into a good Hindu lifestyle. Castro (that was his unlikely name) reasserts that ‘Hinduism is not a religion it is a way of life’. Albeit that he agrees many modern-day devotees forget this and see a visit to the temple as a quick fix for their aberrant behaviour, rather than a source of energy to enable them to continue with the devotions their faith demands.

We head back for dinner at the Heritage and a bottle of British Empire beer, at 8% not to be messed with. The buffet is delicious and shared with friends from Devon who we bumped into unexpectedly by the hotel pool.

The question we are asked by strangers here and everywhere is ‘where you from?’

A logical question to a pale westerner wearing European clothing. I know how to answer: ‘that is an outrageous question, and I am deeply offended that you ask it. You are making unacceptable judgments about my cultural roots and ethnic background which I find distasteful and demeaning.’

What I actually say, willingly and with a smile, is that we come from England, near Oxford.

Comments