I have visited several War Graves Commission Cemeteries and on each occasion have left feeling crushed by the burden of the past. Two great uncles are buried in the same cemetery in the Somme, (one with C E Pither on the headstone) and I have stood in others in Flanders field with similar emotions. These corners of foreign fields are both desperately sad and incredibly moving. I am not quite sure what it is that provokes this almost spiritual sense of loss and pathos. The beautifully tended lawns and plots, the quiet serenity, the timelessness, the simplicity of the headstones, the bronze fixtures, and perfect Lutyens cross. It is disrespectful to say there is beauty here? I am not sure, but there is more than just the rage and the sadness, the terrible waste of young lives and the futility of war, something other worldly and perpetual. I am minded of Yeats: ‘a terrible beauty is born.’

On return from my first visit I can remember bending my father’s ear about the horrors of the first war and finding him less than receptive. In fact, he took the hump. Later he said something that made be realise why, ‘my war wasn’t fun you know.’

The monument to the 917 Hindu and Sikh service men who were cremated

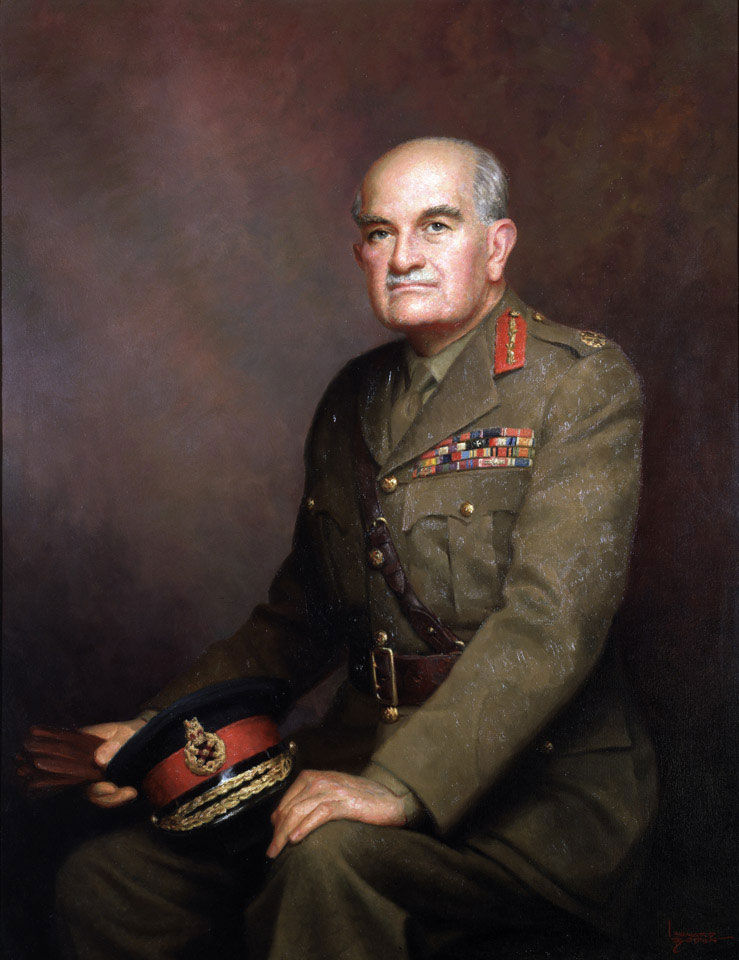

Now we stand in the War Cemetery in Kohima where 1420 allied servicemen are buried, and both the above observations coalesce. Although Father didn’t see the thick of the fighting in Burma, he fought here, arriving with the 50th Armoured division by sea at Maungdaw and pushing inland, flushing out the last few Japanese dugouts in the hills of the Arakan, before being pulled back in his Abrams tank to fight elsewhere. He was close enough to the South Eastern Asian theatre to know of its horrors and barbary, of what jungle warfare was like in the monsoon and to have the Japanese of then as a foe. He also felt proud to have been commanded by Bill Slim, a soldier’s general, a sentiment shared by all who served under him.

After the rout of Singapore, the Japanese swept through Burma finding the disorganised and sparse British forces ill-equipped and untrained in the type of jungle warfare the Japanese exploited. The Brits had no option but to retreat, something they tried to do in a staged orderly fashion to preserve kit and personnel, aims in which they repeatedly failed. They straggled back to Indian soil, reaching safety the far side of the Kohima Imphal Road, accompanied by hundreds of thousands of refugees. The conditions were shocking, even on arrival in what was territorially a safe haven, but practically was a disease-ridden canvas city with no medical care and almost nothing to eat.

It took Slim 18 months to assemble, equip and train a fighting force for the return match. Reading his book From Defeat into Victory I am struck by so many comparisons I don’t want to make between the then and the now, the imperatives of military thinking, the necessity of expediency, the extraordinary need for logistics and engineering support, the leadership and fleetness of decision making to name but a few.

Slim realised that to beat the Japanese at their own game his armies had to learn how to live and fight in the jungle, so arriving troops were kicked out of the barracks and re-billeted to jungle camps where they lived under canvas in the wet, with the leeches, the bitey things and the noises at night. They went on daily patrols clambering steep ridges through the thickest vegetation. Disease was a massive problem with sickness accounting for greater loss of manpower than injury. He insisted that long sleeves were worn, no showers were taken after dark and anti-malarials were taken. He wrote:

'Good doctors are no use without good discipline. More than half the battle against disease is fought not by doctors, but by regimental officers. It is they who see that the daily dose of mepacrine is taken. If mepacrine was not taken, I sacked the commander. I only had to sack three; by then the rest had got my meaning.'

But it wasn’t just health that came under the Generals remit. The food was terrible, with the heat turning bully beef into a sludgy soup and nothing fresh or green. He organised local supplies to supplement service issue. Then there were the parachutes. The planned advance back into Burma (along with supplying the Chinese army to the north via ‘the hump’) was going to crucially depend on airlifts provided by Dakotas piloted by the USAF, but silk parachutes were not available due to the requirements for D-day. Slim had to have parachutes. Two local options were tabled as possibilities: paper parachutes from the mills in Calcutta or Jute available locally. The mills in Calcutta couldn’t reorganise their machinery in time, so it had to be jute. But could you make a parachute from a sack? Within three days Slim had three different prototype parachutes to trial. One worked well enough to be used for resilient equipment. He had his first batch within a week. Ultimately, they used a million of these chutes at a pound a go. The silk ones cost £25.

By the beginning of 1944 Slim thought his army was up to the task. There were still numerous logistic and supply issues that limited his choices, (like obtaining enough boats for a seaborn assault) but plans for the invasion were taking shape. However, he knew that Mugaguchi (the Japanese General) was planning an attack from Northern Burma. Slim chose the Kohima Imphal ridge at the site of his defence and started planning for the impending attack. Intelligence suggested that the enemy would not directly attack Kohima and couldn’t reach it until mid-April. This proved to be wishful thinking, as on the 4th April the 2500 unprepared personnel, (including 1000 non-combatants) defending the ridge came under artillery and mortar fire. This was the start of what has been described as ‘Britain’s greatest battle’.

Progressively the Japanese encroached on the defended areas such that the perimeter shrank day by day. Each onslaught was a ferocious encounter fought at close quarters, as small numbers of the 15000 strong Japanese force would rush the entrenched positions of the West Kent Regiment. Sometimes as in the first war, entrenched positions changed hands repeatedly.

The diorama from the excellent Kohima War Museum, looking down to the tennis court with the burnt out Deputy Commissioners bungalow below. Thee British positions are in the foreground, the Japanese the other side of the court.

By the end of the first week the perimeter had retracted to an area around Garrison Hill and the district commissioner’s bungalow below. In between was the tennis court. The water supply had been cut off with the Japanese advance, and water became critically short, with a ration of less than a pint a day. Air drops containing crucial items and water missed their targets, the field hospital was hit by artillery fire killing medical staff and reinjuring the wounded. There was no morphine, and other crucial medical supplies were desperately short. There was no way of evacuating the wounded save for stretcher parties at night by exhausted bearers.

The tennis court visible to the left of the monument, looking down from Garrison Hill over Kohima town.

And then it got even worse. The Japanese advanced past the Deputy Commissioners bungalow to reach the slope beneath the tennis court, the British were dug in the other side. The allied area was now no more than 350 square metres, the combatants close enough to be able to lob grenades at each other. In between were the dead and dismembered torsos. Survivors remembered the impossible number of flies and the clinging stench of death which permeated everything. Wave after wave of suicidal attackers rushed the defenders by both day and night. They were often repulsed on the end of a bayonet. By the 16th of April the men were on their knees, dehydrated, sleep deprived, and starving without access to a proper meal or even a cup of tea. Death was everywhere. Neither side had been able to bury their dead for nearly two weeks. It rained heavily soaking man and mountain. A supply drop containing mortar ammunition, (which had run out) and water, missed the target zone. The defenders doubted they would be able to repulse the next push, morale sagged with the growing sense of the inevitable. The Japanese did not take prisoners. But miraculously the assault never came. The Japanese had launched their rapid advance with only three weeks rations and ammunition, they were in no better state than the British. And then on the 19th the troops of the 161st Indian Brigade broke through securing the road and were able to relieve the garrison. They found a scene of biblical ghastliness, to compare with anything the first war had to offer.

This wasn’t the end of the battle. Far from it, the fighting around Kohima persisted for another month with great loss of life for the allies. The Kohima Imphal road was not secured until June 22nd with the meeting of the two allied forces at milestone 109, captured by one of the very few photos of the battle. But the tide had been turned. The cherry tree next to the Deputy Commissioner’s tennis court still exists as a monument to the furthest the Japanese army advanced into India. Slim marched south to engage the enemy and gradually the battle for Burma was won. The allies lost 11,000 men at Imphal and 4,000 at Kohima. The Japanese losses were about 55,000.

And some of this is what I am thinking as I stand on the tennis court in the middle of the Kohima War Cemetery. It is beautifully tended, tranquil, reverential, the poignancy is palpable. There are no headstones rather small slanting stones with cast brass plaques. The central cross is placed on the tennis court itself, the lines of which are marked in low concrete ridges. The previous emotions rise unbidden and I sob while nobody is looking, prompted by the young lives cut short, the sacrifice they made, but also the unquestioning permanence of the memorial. We will remember them.

But there is something else here, standing in this special place and finally understanding the geography of the battle, I am unable to comprehend the heroism and valour of the men who defended this tiny hillock to the death. Men like the immeasurable John Winstanley, who taught me what little ophthalmology I know. I can’t envisage the ghastliness and the courage, resilience and endurance needed. I couldn’t have done it. I would have crumbled. I would have failed. But these men didn’t. Men of my Dad’s generation summoned something, from God knows where, and did what was asked of them, and so much more. And I am struck by the difference between the world they knew and their values, and the world we inhabit now, and I feel pathetic and small, and I wish I had hadn’t banged on to him so much about the first war.

Garrison Hill after the battle

Comments